HTTP in Computer Networks Explained: Basics, Methods & More

Dec 02, 2025 5 Min Read 2127 Views

(Last Updated)

Have you ever typed a web address, hit Enter, and wondered exactly how that short string turns into a fully rendered page on your screen? Here’s the thing: that invisible handshake between your browser and a remote server is powered by HTTP, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol.

At its core, HTTP in computer networks is a simple, text-based request–response protocol that follows a client-server model, but it packs a lot of practical detail you’ll use again and again: methods (GET, POST, PUT), status codes (200, 404, 500), headers, caching rules, and the evolution from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 (QUIC).

In this article, you’ll get clear, textbook-accurate definitions, concise examples of how HTTP shows up in web apps and APIs, and hands-on pointers so you can inspect and experiment with real requests. So, without further ado, let us get started!

Quick Answer

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the standard protocol that enables communication between web browsers and servers by sending requests and receiving responses. It forms the foundation of how data is transferred on the web, making websites, apps, and APIs work seamlessly.

Table of contents

- What is HTTP in Computer Networks?

- Key Features of HTTP

- How HTTP in Computer Networks Works?

- HTTP Requests and Methods

- What are HTTP Status Codes?

- HTTP vs. HTTPS (Secure HTTP)

- HTTP Versions and Evolution

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- What is HTTP, and how does it work?

- What is the difference between HTTP and HTTPS?

- What are HTTP methods?

- What are HTTP status codes?

- What port does HTTP use?

What is HTTP in Computer Networks?

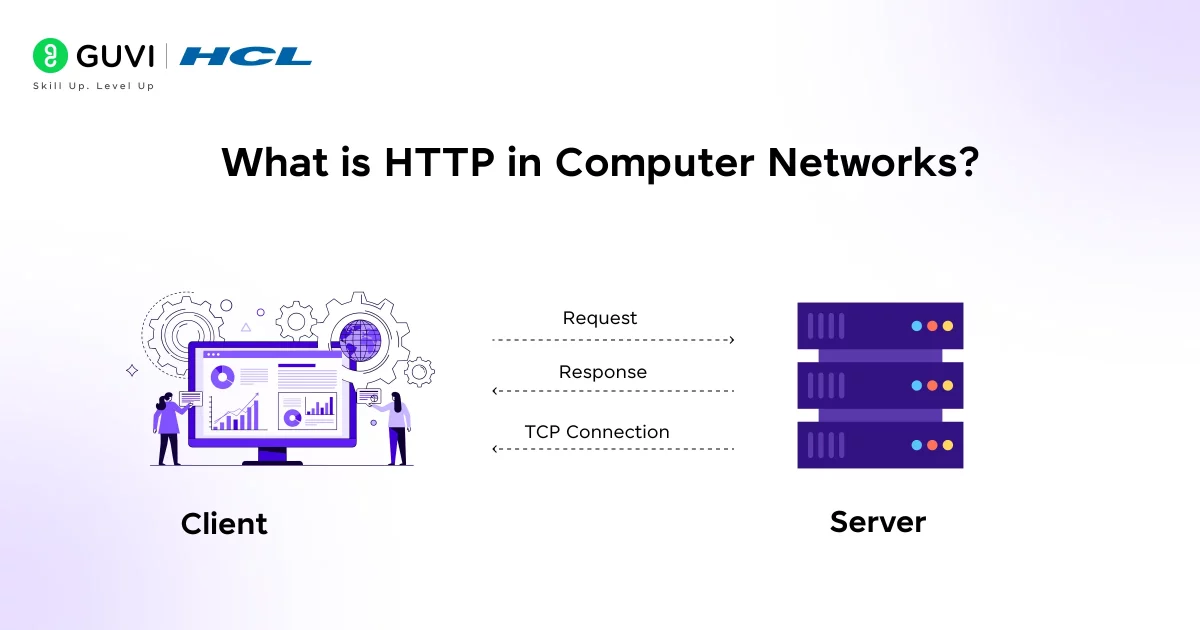

HTTP in computer networks stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol. In practice, this defines how web clients and servers talk to each other. HTTP was created in the early 1990s by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN as the protocol for the World Wide Web. Its job is to standardize how requests (asking for web resources) and responses (delivering those resources) are formatted and exchanged.

- Foundation of the Web: HTTP is the “language” of the web. When you open any website, HTTP is almost certainly the protocol under the hood that delivers the page content to your browser.

- Stateless Protocol: HTTP is stateless, meaning each request the client makes is independent of any previous one. The server does not keep any information (session data) about past requests by the client. For example, if you request the same page twice in a row, the server treats each request anew.

Key Features of HTTP

Some of the basic features that make HTTP work include:

- Client-Server Model: HTTP uses a client–server architecture. The client (usually your web browser or an app) initiates requests, and the server (hosting the website or API) responds. This clear separation allows browsers and servers to evolve independently.

- Statelessness: Each HTTP request is independent. The server doesn’t remember previous requests from the same client. (In effect, after each response, the connection can close if not persistent.)

- Connectionless by Default: In older HTTP versions (like 1.0), each request opened a new TCP connection to the server. HTTP/1.1 introduced persistent connections (keep-alive), so one TCP connection can handle multiple requests in sequence.

If you are curious on how servers handle requests from HTTP, read the blog – How Do Servers Handle Requests? A Comprehensive Guide

How HTTP in Computer Networks Works?

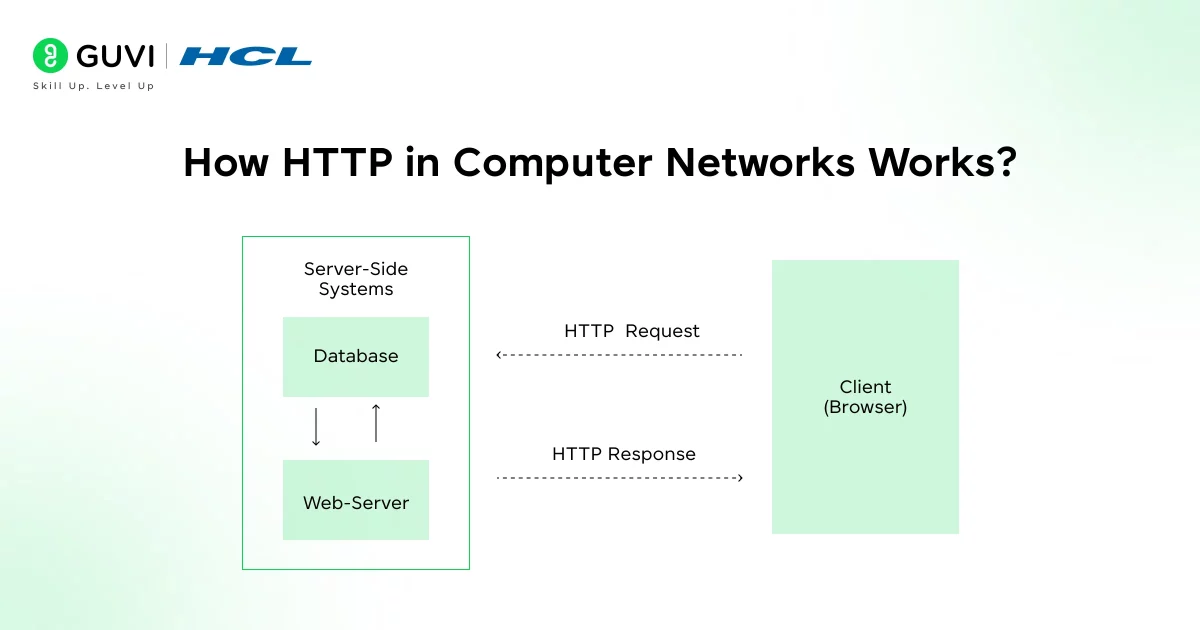

At its core, HTTP is simple: a client sends a request and a server sends a response. Here is a step-by-step look at a typical HTTP transaction:

- Client Sends an HTTP Request: You (the client) ask for something. For example, you enter http://example.com/index.html in your browser. The browser constructs an HTTP request message that includes a request line (with a method like GET, the resource path /index.html, and the protocol version), headers (like Host: example.com, User-Agent, etc.).

- Server Processes the Request: The web server receives this request and processes it. It determines which resource is being requested (e.g., the file index.html) and what the client is asking. It may read the file from disk, run scripts, query databases, or perform other logic to prepare a response.

- Server Sends an HTTP Response: After preparing the data, the server sends back an HTTP response message. This response starts with a status line, for example, HTTP/1.1 200 OK, indicating success. It then includes response headers (like Content-Type, Content-Length, etc.) and finally the message body (e.g. the HTML content of the page). If the requested resource is not found, the server might send 404 Not Found instead.

- Client Receives and Renders: Your browser (the client) receives the response. It reads the status code: if 200 OK, it proceeds to parse the content. The browser then renders the page for you to see. If the response included references to additional resources (images, CSS, scripts), the browser makes additional HTTP requests to fetch those as well, repeating this cycle.

If you want in-depth knowledge about computer networks and don’t know where to start, consider enrolling in HCL GUVI’s Self-Paced Networking Concepts course, which covers essential networking concepts, protocols, and security measures to help upskill your career in IT infrastructure and network management.

HTTP Requests and Methods

An HTTP request has the following structure:

- Request line: Contains the method (action), the resource path (URL), and the HTTP version. e.g. GET /about.html HTTP/1.1.

- Headers: Key-value lines that carry meta-information (like Host:, Accept:, User-Agent:, Authorization:, etc.).

- Body (optional): Data sent with the request, used by methods like POST or PUT.

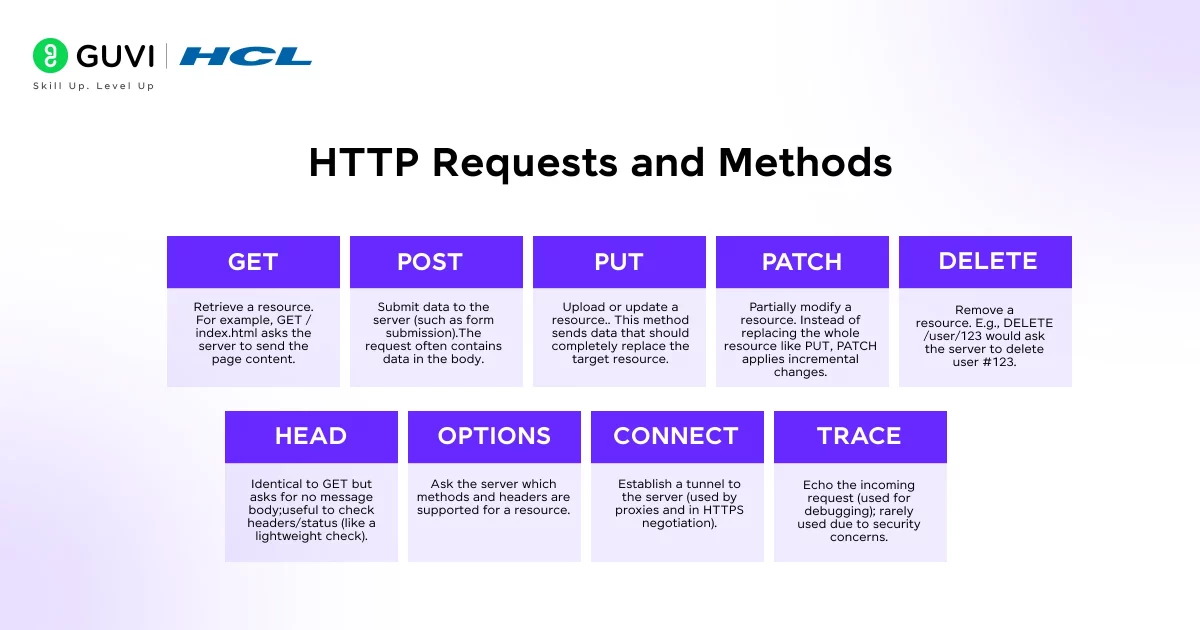

The HTTP methods define what action the client wants to perform on the resource. The most common methods are:

- GET: Retrieve a resource. For example, GET /index.html asks the server to send the page content. It should have no side effects (it doesn’t change the server state).

- POST: Submit data to the server (such as form submission). The request often contains data in the body. The server processes this data (e.g., to create a new record).

- PUT: Upload or update a resource. This method sends data that should completely replace the target resource.

- PATCH: Partially modify a resource. Instead of replacing the whole resource like PUT, PATCH applies incremental changes.

- DELETE: Remove a resource. E.g., DELETE /user/123 would ask the server to delete user #123.

- HEAD: Identical to GET but asks for no message body; useful to check headers/status (like a lightweight check).

- OPTIONS: Ask the server which methods and headers are supported for a resource.

- CONNECT: Establish a tunnel to the server (used by proxies and in HTTPS negotiation).

- TRACE: Echo the incoming request (used for debugging); rarely used due to security concerns.

These methods are key to HTTP’s flexibility. For example, reading a blog post is done with GET, submitting a login form might use POST, and updating your profile picture could use PUT or POST.

What are HTTP Status Codes?

When the server responds, it always includes a status code (a 3-digit number) that tells the client how the request went. These codes are grouped into five categories:

- 1xx (Informational): Request received, continuing process (rarely used).

- 2xx (Success): The request was successfully received and processed.

- 200 OK – Standard response for successful GET or POST.

- 201 Created – A new resource was successfully created (often after a POST).

- 204 No Content – Request succeeded, but there is no content to return (for DELETE, PUT without response body, etc.).

- 200 OK – Standard response for successful GET or POST.

- 3xx (Redirection): Further action needed.

- 301 Moved Permanently – The resource has a new URL.

- 302 Found – Temporary redirect.

- 304 Not Modified – Resource not modified; use cached version.

- 301 Moved Permanently – The resource has a new URL.

- 4xx (Client Error): The request was invalid or cannot be fulfilled by the server.

- 400 Bad Request – Server could not understand the request.

- 401 Unauthorized – Authentication required or failed.

- 403 Forbidden – Server refuses to fulfill.

- 404 Not Found – The requested resource isn’t available on the server.

- 418 I’m a teapot – (An Easter egg status code from an April Fools joke; rarely seen in practice.)

- 400 Bad Request – Server could not understand the request.

- 5xx (Server Error): The server failed to fulfill a valid request.

- 500 Internal Server Error – General server failure.

- 502 Bad Gateway, 503 Service Unavailable – Server cannot handle request (overloaded or down), etc.

- 500 Internal Server Error – General server failure.

For example, if you try to load a page that doesn’t exist, the server will send 404 Not Found along with a “Not Found” page. If a request is successful, you’ll see 200 OK. Web developers use these codes to understand what’s happening in the background.

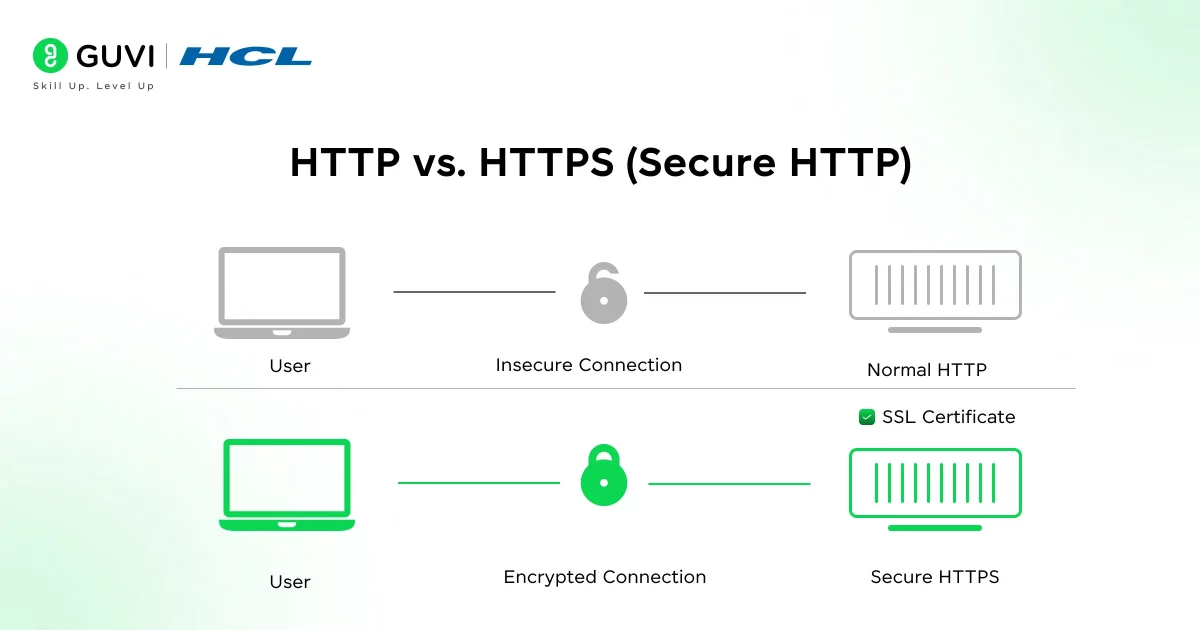

HTTP vs. HTTPS (Secure HTTP)

HTTP by itself sends everything in plaintext over the network. This means an attacker sniffing the network could read the contents of requests and responses (including passwords, cookies, etc.).

To protect privacy and security, HTTPS was introduced. HTTPS means “HTTP over TLS/SSL”: before any HTTP data is exchanged, the client and server perform an encryption handshake using SSL/TLS. All subsequent HTTP messages (requests and responses) are then encrypted.

In practice, HTTPS works almost exactly like HTTP at the protocol level, except the entire TCP connection is secured with encryption. The URL starts with https:// and the default port is 443 (instead of 80). When you visit an HTTPS site, your browser first checks the server’s digital certificate (issued by a trusted authority) to authenticate the server. Once the TLS tunnel is established, your GET and POST data travels encrypted.

Today, HTTPS is so important that browsers and search engines favor HTTPS by default. For example, Google’s search ranking gives a slight boost to HTTPS sites, and browsers show a padlock icon for HTTPS pages.

HTTP Versions and Evolution

Since its birth, HTTP has evolved in several versions:

- HTTP/0.9 (1991): The extremely simple and very first version. It only supported the GET method and had no headers or status codes.

- HTTP/1.0 (1996): Introduced headers (like Host, User-Agent) and status codes. Each request still opened a new connection (no reuse).

- HTTP/1.1 (1999): Became the dominant standard. It added persistent connections (so multiple requests could reuse one TCP connection), pipelining (sending multiple requests without waiting for each response), chunked transfers, more methods and headers, and caching controls.

- HTTP/2 (2015): A major update that keeps the same basic semantics (methods, status codes, URIs) but changes the underlying format to be more efficient. HTTP/2 is binary instead of text, allows multiplexing many requests/responses over one connection, uses header compression, and supports server push.

- HTTP/3 (2022): The newest version, which uses QUIC (a UDP-based transport) instead of TCP. HTTP/3 offers lower latency and faster page loads in many cases. It integrates encryption and can recover from packet loss faster than TCP. It’s already supported by most browsers and servers.

The original version of HTTP, called HTTP/0.9, only supported one command: GET, and it didn’t even include headers or status codes. It was so minimal that every response was just raw HTML with no metadata. Fast forward to today, and we have HTTP/3 running over QUIC, enabling faster, more reliable connections even on spotty networks like mobile or Wi-Fi.

If you’re curious to learn all about Computer Networks and want to apply it in real-world scenarios, don’t miss the chance to enroll in HCL GUVI’s IITM Pravartak and MongoDB Certified Online AI Software Development Course. Endorsed with NSDC certification, this course adds a globally recognized credential to your resume, a powerful edge that sets you apart in the competitive job market.

Conclusion

In conclusion, HTTP in computer networks is the key protocol that makes web browsing and online communication possible. It’s simple in concept but also very powerful and flexible. As you start learning networking or web development, understanding HTTP is essential.

Once you understand the request–response model, the common methods, status codes, headers, and the role of HTTPS (TLS) for security, you’ll be able to read network traces, troubleshoot problems, and make smarter design choices for web apps and APIs.

FAQs

1. What is HTTP, and how does it work?

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the standard protocol used for transferring data on the web. It works on a client-server model where your browser sends requests and servers return responses.

2. What is the difference between HTTP and HTTPS?

HTTPS is the secure version of HTTP, using SSL/TLS encryption to protect data in transit. It ensures privacy and prevents tampering during communication.

3. What are HTTP methods?

HTTP methods define the type of action to perform on a resource; common ones include GET (retrieve), POST (submit), PUT (update), and DELETE (remove).

4. What are HTTP status codes?

They are three-digit numbers in server responses indicating request outcomes—e.g., 200 (OK), 404 (Not Found), 500 (Server Error).

5. What port does HTTP use?

HTTP uses port 80 by default, while HTTPS uses port 443 for secure communication.

Did you enjoy this article?