Bias and Ethical Concerns in Machine Learning

Oct 17, 2025 6 Min Read 872 Views

(Last Updated)

Have you ever wondered why supposedly “objective” algorithms sometimes make unfair or biased decisions, like misidentifying faces, rejecting qualified candidates, or ranking students inaccurately?

The truth is, machine learning systems don’t see the world as neutral; they see patterns in data that reflect our human choices, histories, and inequalities. That’s what makes bias and ethical concerns in machine learning so critical to understand.

As ML becomes embedded in education, healthcare, hiring, and governance, it’s no longer enough for models to just be accurate; they need to be fair, transparent, and accountable. The question isn’t whether bias exists, but how we detect, manage, and take responsibility for it. That is what we are going to see in this article!

Table of contents

- What Do We Mean by Bias?

- Types of Bias

- What Ethical Frameworks & Principles Guide Us?

- Fairness and Equity

- Transparency and Explainability

- Accountability and Responsibility

- Privacy and Data Governance

- Non-Maleficence (Do No Harm)

- Human Oversight

- Inclusivity and Participatory Design

- Detecting & Mitigating Bias and Ethical Concerns in Machine Learning: A Roadmap

- Preprocessing: Tackling Bias in Data

- In-Processing: Modifying the Model Itself

- Post-Processing: Adjusting Outputs

- Evaluation and Ongoing Monitoring

- Governance & Organizational Practice

- Trade-offs, Limitations & Open Challenges

- Fairness vs. Accuracy

- Conflicting Definitions of Fairness

- Context Dependency

- Hidden or Proxy Bias

- Feedback Loops

- Interpretability vs. Performance

- Ethical Fatigue and Tokenism

- What You Can Do (As a Practitioner or Stakeholder)

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- What causes bias in machine learning?

- Can bias in machine learning be completely eliminated?

- How do you detect bias in a model?

- What are the main ethical issues in machine learning?

- What’s the biggest challenge in achieving fairness in AI?

What Do We Mean by Bias?

When people hear “bias in ML,” some think the algorithm is “prejudiced,” which is partly true, but that term misses nuance. Bias in Machine Learning refers to systematic deviations that cause unfair or unintended outcomes, especially for certain groups.

Types of Bias

Bias in ML can manifest in many forms. Here are some common ones:

- Data Bias: When the data you train on doesn’t reflect the real world. Think of it as teaching from a one-sided textbook.

- Sampling Bias: Some groups show up too much, others barely appear. Your model ends up knowing some people way better than others.

- Measurement or Labeling Bias: If the data labels or features are collected unfairly or inconsistently, your model learns those same mistakes.

- Algorithmic Bias: Even with balanced data, the model’s math or objective function can tilt outcomes toward certain groups.

- Feature or Proxy Bias: Sometimes harmless-looking features (like zip code) secretly act as stand-ins for sensitive traits (like race or income).

- Interaction or Feedback Bias: Once deployed, your model changes how people behave, and that new behavior feeds right back into the model, reinforcing bias.

Researchers often group bias sources into three buckets: data bias, development bias, and interaction bias.

What Ethical Frameworks & Principles Guide Us?

When you’re building or deploying machine learning systems, ethics isn’t just a moral checkbox. It’s a design principle. Ethical frameworks help you decide what “responsible AI” looks like in practice, not just whether your model is accurate.

Let’s go over the key principles that most AI ethics frameworks share and what they actually mean for you.

1. Fairness and Equity

Fairness means your model’s predictions or decisions shouldn’t systematically disadvantage specific groups or individuals.

But fairness isn’t one-size-fits-all. Depending on context, you might define it differently:

- Demographic parity: Outcomes are equally distributed across groups.

- Equal opportunity: Everyone has the same chance of a positive result given equal qualifications.

- Individual fairness: Similar individuals should be treated similarly.

The tricky part? You can’t satisfy every fairness definition at once. So ethical design often means being explicit about which fairness metric you’re optimizing for and why.

2. Transparency and Explainability

AI systems can be complex black boxes. Ethical frameworks emphasize that you must make them understandable to users, regulators, and your own team.

Explainability serves multiple roles:

- Builds trust with users and stakeholders.

- Enables accountability if something goes wrong.

- Helps debug or identify bias internally.

You don’t need to make every model 100% interpretable, but you should be able to answer: why did this decision happen, and on what basis?

3. Accountability and Responsibility

Who’s accountable when a model causes harm: the developer, the company, or “the AI”? The answer can’t be “no one.”

Ethical ML frameworks insist on clear lines of responsibility:

- Identify decision points where humans should remain “in the loop.”

- Maintain documentation of data sources, modeling choices, and fairness tests.

- Ensure teams are trained to understand the ethical implications of their work.

In short: Accountability is about owning outcomes, not just code.

4. Privacy and Data Governance

Bias isn’t the only ethical risk. Privacy is right beside it. An ethical system ensures that user data is:

- Collected with consent and transparency.

- Stored securely and used responsibly.

- Processed with mechanisms like anonymization or differential privacy.

Even anonymized data can reveal sensitive traits through correlations — so “ethical data governance” means managing risk, not just ticking compliance boxes.

5. Non-Maleficence (Do No Harm)

Borrowed from medical ethics, this principle reminds us: don’t deploy models that can cause foreseeable harm.

That includes:

- Reinforcing stereotypes

- Excluding marginalized groups

- Producing unsafe recommendations

- Enabling surveillance or misuse

6. Human Oversight

No matter how advanced your system is, humans must stay involved. Machine learning models can’t interpret context or ethics the way people can.

Human oversight ensures:

- Interventions when models go wrong

- Appeals processes for affected users

- Continuous evaluation beyond technical metrics

7. Inclusivity and Participatory Design

You can’t design fair systems in isolation. Involve diverse voices: data subjects, domain experts, affected communities. Why? Because ethical blind spots often come from limited perspectives. Inclusion early in design helps you identify risks that aren’t visible from a purely technical angle.

In short: ethics in ML is about building systems that are fair, transparent, accountable, respectful of privacy, and aligned with human well-being, not just technically “good.”

If you are interested to learn the Essentials of AI & ML Through Actionable Lessons and Real-World Applications in an everyday email format, consider subscribing to HCL GUVI’s AI and Machine Learning 5-Day Email Course, where you get core knowledge, real-world use cases, and a learning blueprint all in just 5 days!

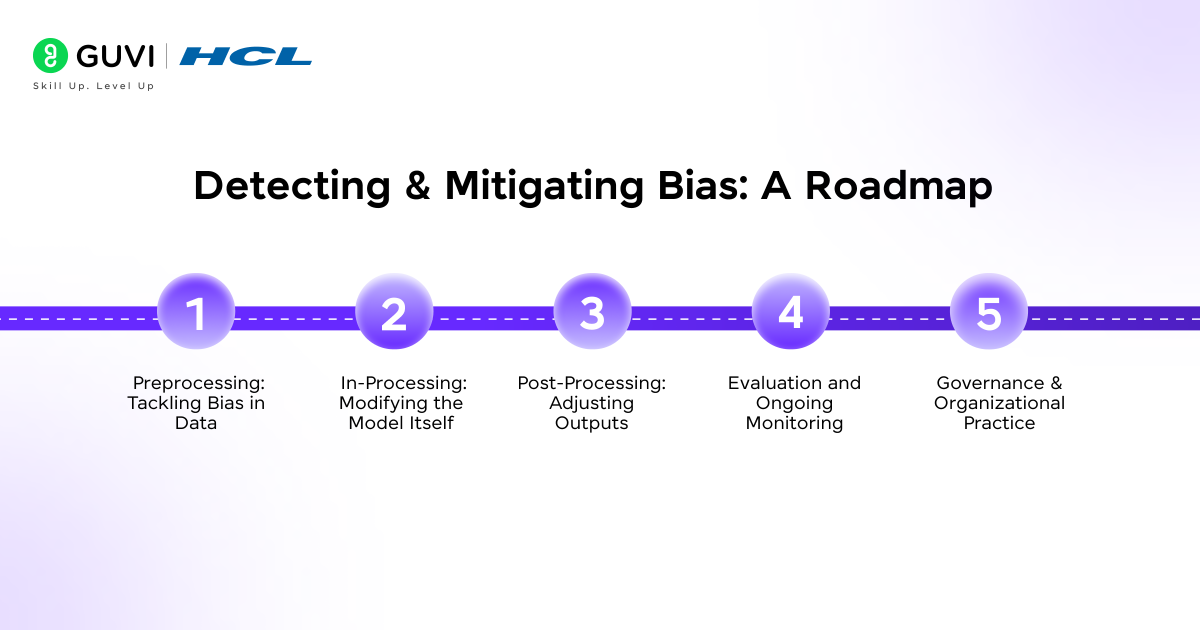

Detecting & Mitigating Bias and Ethical Concerns in Machine Learning: A Roadmap

Bias mitigation isn’t a one-time patch. It’s a continuous process woven into every stage of the ML pipeline from data collection to deployment. Here’s what that looks like step-by-step.

1. Preprocessing: Tackling Bias in Data

Most bias starts here. Your data reflects the world, and the world isn’t neutral.

Key actions:

- Audit your data: Analyze representation across gender, race, age, geography, etc. Use descriptive stats or fairness dashboards.

- Handle imbalance: Reweight or resample to avoid dominant group overrepresentation.

- Review labeling: Were labels assigned fairly? Labeling bias often hides in “human judgment” stages.

- Use synthetic data carefully: It can balance representation but might introduce artificial correlations.

- Document your dataset: Include origin, intended use, and known limitations (Datasheets for Datasets is a good framework).

Goal: ensure your training data gives every group a fair chance to be learned.

2. In-Processing: Modifying the Model Itself

Once you have data, bias can still creep in during training — through objective functions, regularization, or model structure.

Methods:

- Fairness constraints: Integrate fairness metrics (e.g., equalized odds) into your loss function.

- Adversarial debiasing: Train the model to make predictions while preventing a secondary adversary from predicting protected attributes.

- Causal modeling: Understand which features cause predictions, not just correlate with them.

- Representation learning: Learn embeddings that minimize sensitive attribute information.

This stage is where you mathematically formalize fairness, not just check for it afterward.

3. Post-Processing: Adjusting Outputs

If you can’t change the model (e.g., it’s already deployed or proprietary), you can adjust predictions after the fact.

Examples:

- Calibrate scores separately for each group.

- Change thresholds to equalize false positive or false negative rates.

- Reassign outcomes probabilistically to achieve parity metrics.

These are less ideal but practical for deployed systems.

4. Evaluation and Ongoing Monitoring

Bias detection isn’t a one-off audit; it’s a continuous feedback loop.

What to monitor:

- Performance across subgroups (accuracy, recall, precision, etc.).

- Fairness metrics:

- Demographic parity (same rate of positive outcomes)

- Equal opportunity (same true positive rates)

- Predictive parity (same precision per group)

- Demographic parity (same rate of positive outcomes)

- User feedback and complaint patterns.

- Data drift: new input distributions may reintroduce bias.

Tooling tip: Use open frameworks like IBM’s AI Fairness 360, Google’s What-If Tool, or Microsoft’s Fairlearn.

5. Governance & Organizational Practice

Ethics isn’t just code: it’s culture. Organizations should formalize processes for fairness governance:

- Create internal ethics review boards.

- Integrate fairness checks into MLops pipelines.

- Require documentation (“Model Cards”) for every model deployment.

- Perform regular third-party audits.

- Define escalation processes for ethical risks.

Bottom line: bias mitigation must be systemic, not just technical.

Trade-offs, Limitations & Open Challenges

Bias mitigation sounds straightforward in theory, but in practice, it’s full of trade-offs. Here’s what you’ll face once you move beyond textbook solutions.

1. Fairness vs. Accuracy

Sometimes improving fairness means lowering raw model accuracy. Why? Because fairness constraints may force the model to sacrifice predictive power for one group to equalize outcomes overall.

The key question becomes: how much accuracy are you willing to trade for fairness?

In high-stakes domains (like credit or healthcare), a small accuracy hit might be worth the social gain. But that trade-off must be deliberate and transparent.

2. Conflicting Definitions of Fairness

Here’s something most papers don’t emphasize: you can’t satisfy all fairness metrics simultaneously.

For example:

- Equalizing false positive rates across groups can break predictive parity.

- Enforcing demographic parity can distort real qualification differences.

So you have to choose your fairness lens: guided by legal, ethical, and contextual factors.

3. Context Dependency

What counts as “fair” depends on the domain:

- In lending, you want equal access to credit.

- In healthcare, you prioritize equal accuracy of diagnosis.

- In hiring, you focus on equal opportunity.

The same fairness metric might make sense in one domain but backfire in another.

4. Hidden or Proxy Bias

Even after removing sensitive variables like gender or race, your model can infer them indirectly from proxies – zip code, name, education level, etc. This makes it hard to fully “debias” data without understanding the causal relationships between features.

5. Feedback Loops

Deployed models can reinforce the very patterns they learn.

Example: a predictive policing algorithm directs more patrols to certain neighborhoods → generates more data from those areas → confirms the system’s bias → cycle repeats.

Mitigating feedback bias requires monitoring the impact of model decisions on future data.

6. Interpretability vs. Performance

Deep learning models are powerful but opaque. Simpler models (like decision trees) are easier to explain but might perform worse. You often face a trade-off between interpretability and accuracy, and depending on the use case, transparency might be more important than perfection.

7. Ethical Fatigue and Tokenism

Ethical AI is becoming a buzzword. Some teams create “ethics boards” without real authority or audit trails. This ethics washing, performing fairness for optics, undermines real accountability.

Ethical machine learning isn’t about building a perfect system; it’s about making conscious, transparent, and justifiable trade-offs.

What You Can Do (As a Practitioner or Stakeholder)

You’re not powerless here. Whether you’re designing, reviewing, or deploying ML systems:

- Start with diverse teams. Different perspectives catch more blind spots.

- Be rigorous about data collection: think about inclusion from the start.

- Build bias detection and mitigation into your development lifecycle, not just as an afterthought.

- Use interpretable or explainable models when the stakes are high.

- Keep humans in the loop, especially for high-impact decisions.

- Set up audits, monitoring, feedback channels, and redress mechanisms.

- Engage stakeholders early—ask those affected what fairness means to them.

- Stay updated on research, legal frameworks, and ethical guidelines (e.g., the Toronto Declaration).

In one famous experiment, Google’s image recognition system misclassified photos of Black people more often than White people, because the training data had fewer dark-skinned faces.

If you’re serious about mastering machine learning and want to apply it in real-world scenarios, don’t miss the chance to enroll in HCL GUVI’s Intel & IITM Pravartak Certified Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning course. Endorsed with Intel certification, this course adds a globally recognized credential to your resume, a powerful edge that sets you apart in the competitive AI job market.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ethical machine learning isn’t a destination; it’s an ongoing discipline. No model is perfectly neutral, and no dataset is entirely pure. But awareness and accountability change everything.

When you build with fairness in mind, document your decisions, and include diverse perspectives, you shift ML from being a mirror of existing bias to a tool for more equitable outcomes.

As technologists, educators, and decision-makers, the goal isn’t to eliminate bias; it’s to understand its roots, minimize its harm, and ensure that every automated decision still reflects human values. That’s how we make machine learning not just intelligent, but just.

FAQs

1. What causes bias in machine learning?

Bias usually stems from unbalanced or flawed training data, biased labeling, or feedback loops that reinforce existing patterns in the real world.

2. Can bias in machine learning be completely eliminated?

Not entirely. You can reduce and monitor bias, but since data reflects human behavior and history, some level of bias will always exist.

3. How do you detect bias in a model?

By comparing model performance across demographic groups, using fairness metrics, or tools like IBM AI Fairness 360 and Google’s What-If Tool.

4. What are the main ethical issues in machine learning?

Common issues include unfair treatment of groups, lack of transparency, privacy violations, and lack of accountability in automated decisions.

5. What’s the biggest challenge in achieving fairness in AI?

Balancing fairness with accuracy. Improving fairness for one group can sometimes reduce performance for another, creating tough trade-offs.

Did you enjoy this article?