Introduction to Hierarchical Clustering: A Simple Guide

Sep 23, 2025 6 Min Read 1151 Views

(Last Updated)

Have you ever wondered how Netflix groups similar movies for you, or how Amazon knows your shopping preferences? At the heart of both problems lies the same technique: hierarchical clustering.

It’s a method in machine learning that doesn’t just tell you which items belong together, but also shows how those groupings form at different levels. Think of it like building a family tree for your data, starting from individuals and gradually merging them into larger families.

This approach gives you the freedom to explore patterns without deciding upfront how many groups you want, making it a powerful tool for data exploration. This is what we are going to see in-depth about in this article. So without any delay, let’s get started!

Table of contents

- What is Hierarchical Clustering?

- Types of Hierarchical Clustering

- Agglomerative (Bottom-Up) Clustering

- Divisive (Top-Down) Clustering

- Applications of Hierarchical Clustering

- Advantages and Limitations of Hierarchical Clustering

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- What’s the difference between hierarchical clustering and k-means?

- How do I decide how many clusters I need in hierarchical clustering?

- Can hierarchical clustering handle categorical data?

- Is hierarchical clustering suitable for large datasets?

- How does hierarchical clustering handle outliers?

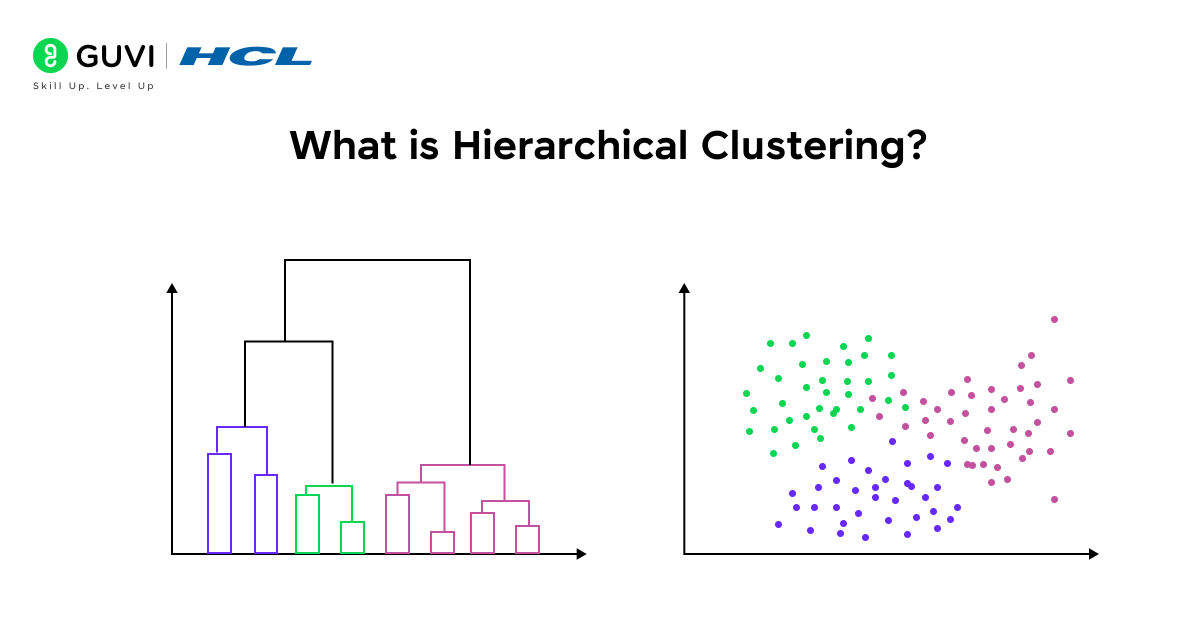

What is Hierarchical Clustering?

Hierarchical clustering is an unsupervised machine learning method that groups data points into a hierarchy of nested clusters.

Instead of producing a flat set of clusters (as algorithms like k-means do), hierarchical clustering builds a tree-like structure of clusters, often visualized as a dendrogram (tree diagram) showing how clusters are merged or split at different levels. In simple terms, it creates clusters within clusters, and smaller clusters merge into bigger ones (or big clusters split into smaller ones) based on the similarity between data points.

Hierarchical clustering is particularly useful for exploring complex datasets because it doesn’t force the data into a predetermined number of clusters. In fact, one big advantage is that you do not need to specify the number of clusters in advance – the algorithm will produce a complete hierarchy, and you can decide later how many clusters fit your needs.

Hierarchical clustering has been around for decades and has its roots in fields like biology. In fact, much of the early work (1950s–1960s) on clustering was driven by biological taxonomy, using hierarchical methods to classify organisms. By the late 1970s, researchers noted that roughly 75% of published clustering studies were using hierarchical algorithms, a testament to how prevalent this approach was in the early days of cluster analysis!

Types of Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering algorithms come in two flavors, which are essentially opposites:

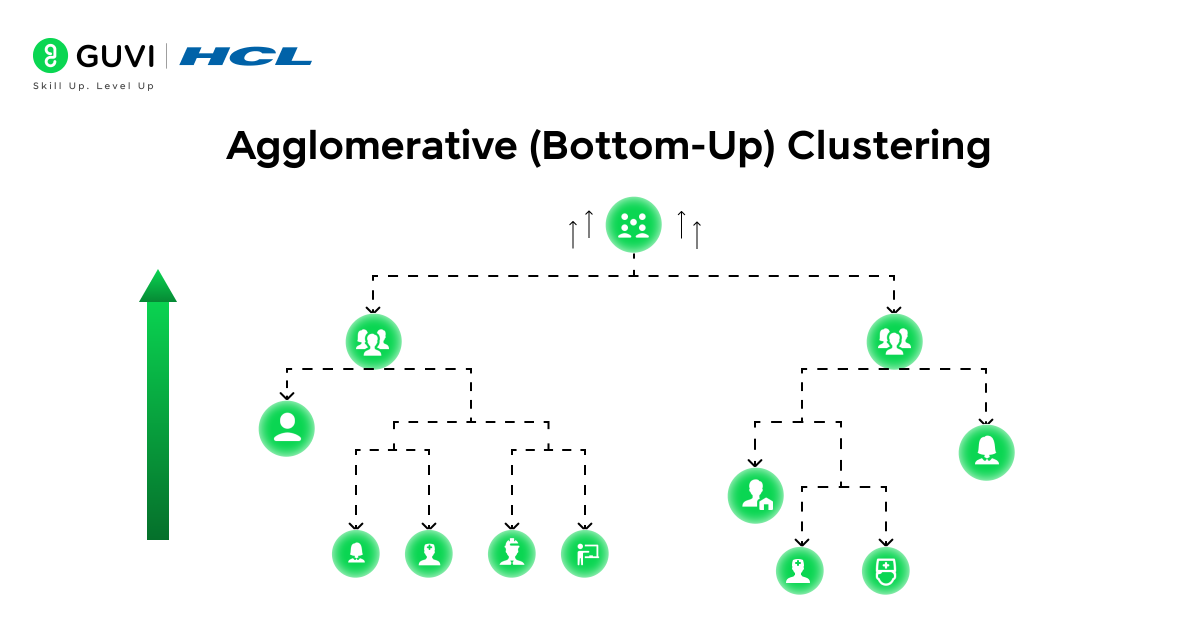

- Agglomerative clustering (Bottom-Up): Start with each data point as its own cluster, then iteratively merge the most similar pairs of clusters until you end up with one big cluster containing everything.

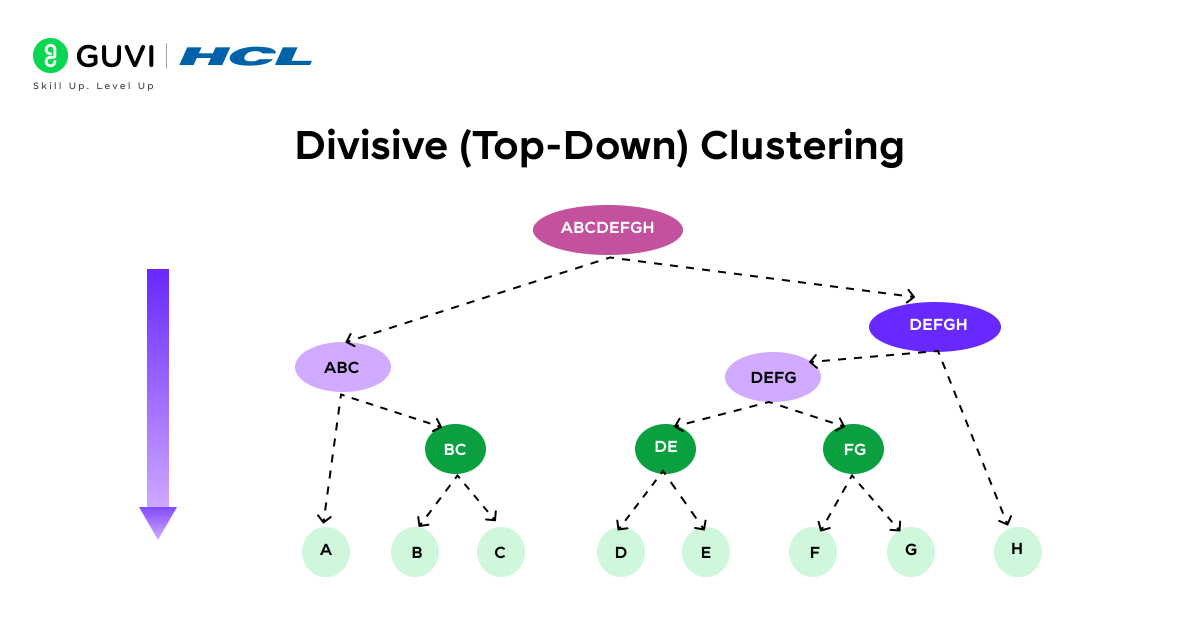

- Divisive clustering (Top-Down): Start with all data points in one cluster, then iteratively split clusters into smaller ones until every point is eventually alone (or until some stopping criterion is reached).

Both approaches yield the same final result – a hierarchy of clusters – but they construct that hierarchy in reverse ways. Agglomerative methods are far more common in practice, so if someone mentions hierarchical clustering, they usually mean the agglomerative (bottom-up) kind by default. Let’s break down each approach:

Agglomerative (Bottom-Up) Clustering

Agglomerative clustering is the bottom-up approach to hierarchical clustering. You begin with the most fine-grained view: every data point is in its own singleton cluster. Then, step by step, clusters are merged based on their similarity.

This continues until ultimately all points belong to one single cluster (the root of the hierarchy). The result is a tree of clusters where each merge represents a higher level of grouping.

How does it work?

On each iteration, the two clusters that are closest (most similar) to each other are merged. “Closeness” is determined by a chosen distance metric (e.g., Euclidean distance) and a linkage criterion.

Initially, when every point is its own cluster, you simply find the two closest points and merge them into a cluster. Then recompute distances between this new cluster and all other clusters, find the next closest pair of clusters, and merge again. This process repeats until only one cluster remains, having unified all data points.

Algorithm steps (simplified):

- Start with each point as its own cluster. If you have N data points, you start with N clusters.

- Compute distances between all clusters (at the start, between all individual points).

- Merge the two closest clusters into a single cluster.

- Update distances: recompute distances between the new cluster and the remaining clusters (according to the linkage method).

- Repeat steps 3–4 until all points are merged into one cluster.

This iterative merging results in a hierarchical grouping. One big benefit of agglomerative clustering is that you don’t need to decide the number of clusters beforehand; you can choose how far to merge (where to stop or cut the dendrogram) after seeing the results.

Also Read: What is a Decision Tree in Machine Learning?

Divisive (Top-Down) Clustering

Divisive clustering takes the opposite approach: it is a top-down method. You start with all data points in one single cluster, then you recursively split that cluster into smaller clusters. Each split attempts to separate points that are least similar to each other into different groups.

If you continue splitting until each point stands alone, you will have the full hierarchy from one cluster down to singletons (which is essentially the same hierarchy you’d get from doing agglomerative merging in reverse).

How does it work?

In practice, divisive clustering is often implemented by using another clustering method for splitting. For example, one might perform a k-means or other flat clustering on the whole dataset to break it into, say, two clusters, then pick one of those clusters and split it further, and so on.

One strategy is to always choose the cluster that is most heterogeneous (e.g., has the largest diameter or error) and split that next. This continues until some stopping condition is met (e.g, a desired number of clusters is reached, or all clusters have become sufficiently small).

Algorithm steps (simplified):

- Start with everything in one cluster.

- Split a cluster into two sub-clusters. This can be done by finding the most distant points within the cluster and separating them, or by using a standard clustering algorithm on that cluster (e.g., splitting via k-means).

- Repeat: choose one of the current clusters that still needs splitting (for example, the cluster with the highest variance or largest size) and split it into two.

- Continue until each data point is isolated in its own cluster, or until you’ve reached a desired clustering granularity.

Divisive clustering tends to be more computationally expensive to do exhaustively, and in practice, it’s less commonly used. In fact, most machine learning libraries don’t have a ready-made implementation of divisive clustering due to its complexity.

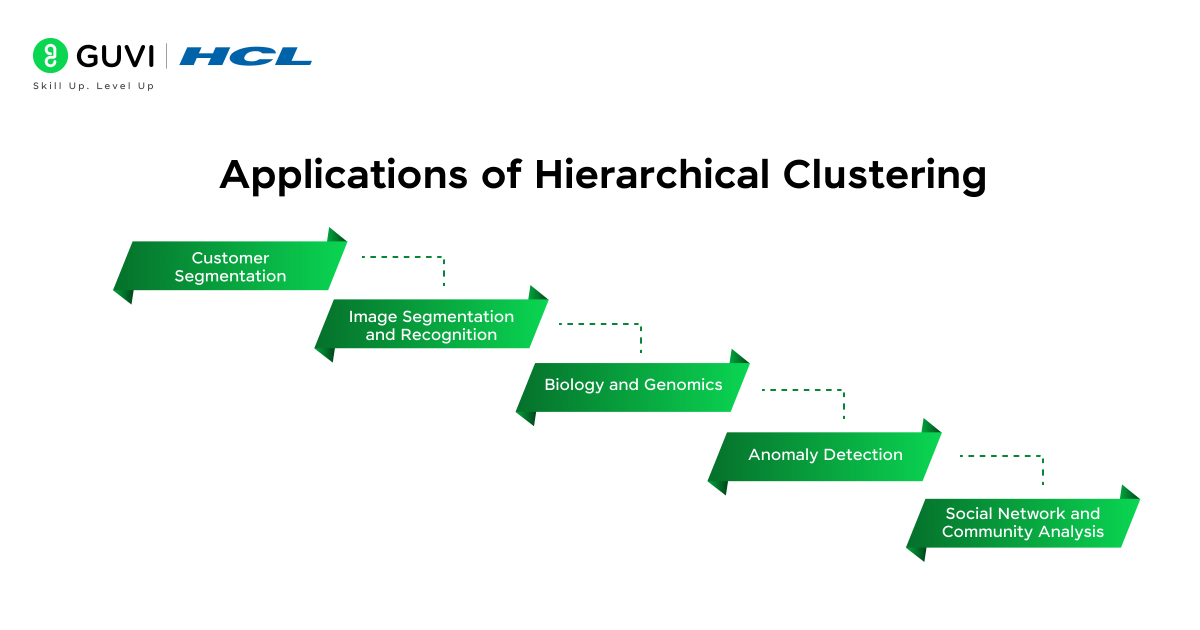

Applications of Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering is a versatile technique and has been applied in many domains. It’s especially handy when the inherent data structure is hierarchical or when you want to explore data without knowing upfront how many clusters you need.

Here are some notable applications and use cases:

- Customer Segmentation: Businesses use hierarchical clustering to group customers into segments based on their behavior or attributes. For example, customers might naturally cluster by purchasing habits, demographics, or interests. By clustering customers, companies can identify target groups and tailor marketing strategies or product recommendations to each group.

- Image Segmentation and Recognition: In image analysis, hierarchical clustering can group similar pixels or features to segment an image into regions. For instance, in a facial recognition context, it might cluster pixels into groups corresponding to facial features (eyes, nose, mouth) by similarity.

- Biology and Genomics: Hierarchical clustering has a long history in biology. Biologists use it to classify organisms (clustering by genetic or physical traits), which essentially produces a taxonomy tree. In modern computational biology, hierarchical clustering is heavily used for gene expression data analysis. Researchers cluster genes that have similar expression patterns across experiments, or cluster samples (e.g., patient tissue samples) by their gene expression profiles.

- Anomaly Detection: Clustering can also help find outliers. Using hierarchical clustering, one can identify data points that never quite merge into a cluster until very high distances (or that form their own singleton clusters at a reasonable cut). These points could be anomalies or outliers.

- Social Network and Community Analysis: In social network analysis (or graph analysis), hierarchical clustering can be used to find communities or groups of nodes. For example, you might cluster people in a social network based on the similarity of their connection patterns. This can reveal a hierarchy of communities, small, tightly-knit groups that merge into larger communities.

These are just a few examples – hierarchical clustering is a general tool, so anytime you have a similarity measure between objects, you can theoretically build a hierarchy.

Explore: Top 10 Machine Learning Applications You Should Know

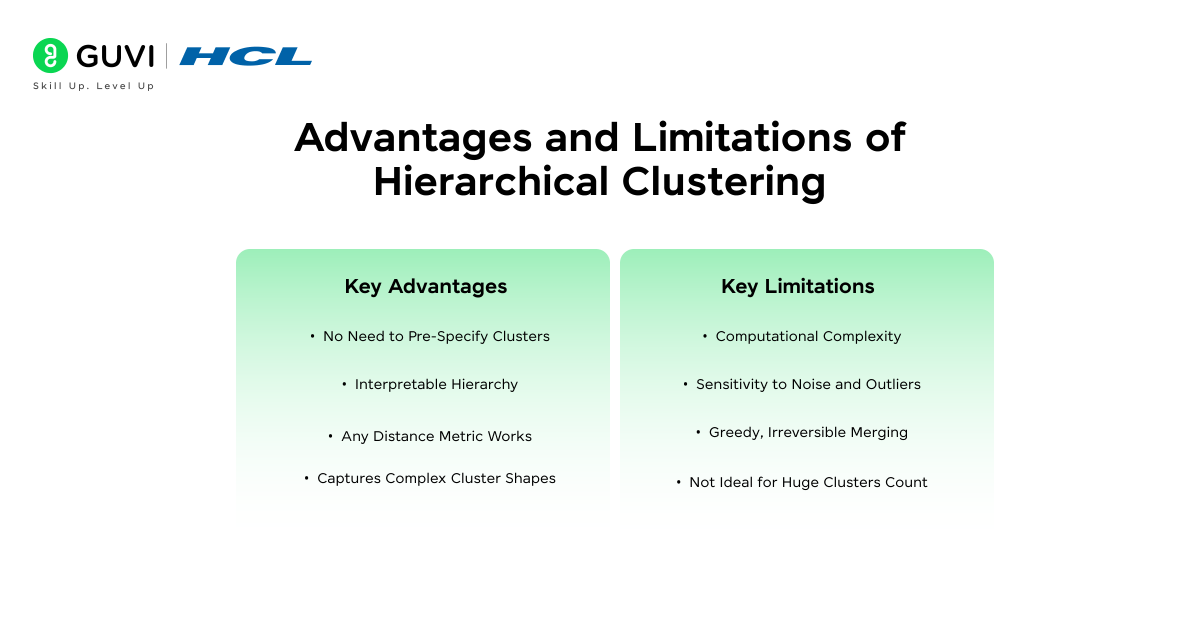

Advantages and Limitations of Hierarchical Clustering

Like any algorithm, hierarchical clustering has its pros and cons. It’s important to understand these to know when hierarchical clustering is the right choice for your problem.

Key Advantages:

- No Need to Pre-Specify Clusters: Unlike k-means or other flat clustering methods, you don’t have to decide on the number of clusters ahead of time.

- Interpretable Hierarchy: The result is a tree of clusters that is often easier to interpret and explain. You can see how clusters merge and what points join a cluster at what distance.

- Any Distance Metric Works: Hierarchical clustering is very flexible in terms of data types and distance measures. It can use any valid distance or similarity measure – even a custom one. You are not restricted to Euclidean distance or to data that lie in a vector space.

- Captures Complex Cluster Shapes: Depending on the linkage method, hierarchical clustering can capture non-convex or irregularly shaped clusters better than k-means. For instance, single linkage can find clusters that form long chains or arbitrary shapes (because it essentially draws clusters together point by point).

Key Limitations:

- Computational Complexity: Hierarchical clustering can be computationally intensive. The naive implementations have time complexity on the order of O(N²) or O(N³) (especially for agglomerative clustering, which in the worst case involves computing an N×N distance matrix and merging N times).

- Sensitivity to Noise and Outliers: Hierarchical clustering can be sensitive to outliers. Since every data point will eventually be forced into the hierarchy, an outlier point can either end up merging with some cluster at a high distance or it might form its own cluster that persists almost until the final merge.

- Greedy, Irreversible Merging: Agglomerative clustering uses a greedy approach – at each step it merges the best pair of clusters based on the current state. Once a merge is done, it cannot be undone. This can lead to local decisions that are suboptimal in the long run.

- Not Ideal for Huge Clusters Count: If your goal is to partition data into a very large number of clusters (say dozens or hundreds), hierarchical clustering might be overkill or even unstable. Small changes in data can sometimes cause changes in the dendrogram structure, which might reorder merges.

Despite these limitations, hierarchical clustering remains a powerful technique for many scenarios. Its strength lies in the rich information it provides (the whole hierarchy) and the flexibility of not having to lock in a particular clustering upfront.

If you’re serious about mastering machine learning concepts like Hierarchical Clustering and want to apply them in real-world scenarios, don’t miss the chance to enroll in HCL GUVI’s Intel & IITM Pravartak Certified Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning course. Endorsed with Intel certification, this course adds a globally recognized credential to your resume, a powerful edge that sets you apart in the competitive AI job market.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hierarchical clustering is more than just another clustering algorithm; it’s a lens to view your data at multiple levels of detail. Creating a hierarchy allows you to zoom in on fine-grained similarities or zoom out to see broad groupings, all within the same framework.

While it comes with limitations like higher computational cost and sensitivity to outliers, its interpretability and flexibility make it a go-to method for many exploratory data analysis tasks.

If you’re working with data and want to understand not just who belongs together but why and how, hierarchical clustering is a technique worth mastering.

FAQs

1. What’s the difference between hierarchical clustering and k-means?

Hierarchical clustering builds a tree-like structure of clusters (a dendrogram), letting you explore groupings at multiple levels without choosing cluster count beforehand. K‑means, on the other hand, requires you to specify the number of clusters in advance and produces flat, non‑hierarchical groupings.

2. How do I decide how many clusters I need in hierarchical clustering?

The common approach is to look at the dendrogram and cut it where there’s a clear gap in merge distances, the so-called “elbow” point, balancing between too few or too many clusters.

3. Can hierarchical clustering handle categorical data?

Yes, but you’ll need a suitable similarity or dissimilarity measure for categorical variables (like Jaccard for binary data or others). Once you have a distance matrix, hierarchical clustering can run without needing numeric features.

4. Is hierarchical clustering suitable for large datasets?

Not always. Since it often computes and stores pairwise distances between every point (O(N²) memory and often worse in time complexity), it can become impractical for very large datasets. For scalability, alternative methods like k‑means, DBSCAN, or sampling-based approaches may be better.

5. How does hierarchical clustering handle outliers?

Hierarchical clustering is sensitive to outliers. Outliers might merge into clusters only at very high distances or form singleton clusters that dominate the dendrogram’s structure. It often helps to preprocess your data to detect or remove outliers first.

Did you enjoy this article?